By Indra Sinha

The Love Teachings of Kama Sutra was the first new English translation of the Kamasutra to be published in the west for nearly a century – it was preceded only by the 1888 translation of Burton and Arbuthnot.

Sometime in the late 1970s I was reading the Burton version and thinking how inadequately the Victorian English represented Vatsyayana’s unembarrassed original, composed in the exuberant Gupta Empire between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE.

It was time for a new translation, that did not treat Vatsyayana’s text as archaic or exotic, but as normal, natural, and modern as today.

Kama Sutra: three common misconceptions

- Kama Sutra is a sex positions manual

- Kama Sutra is an ancient text

- Kama Sutra is a sacred text

- Common misconception #1: Kama Sutra is a sex manual

- Common misconception #2: Kama Sutra is an ancient text

- Common misconception #3: Kama Sutra is a sacred text

- Life in the Gupta Empire

- On society life

- Life in a wealthy Indian household, c350CE

- The 64 arts and sciences

- A tradition of erotic art

- A new approach to translating Vatsyayana

- Indra Sinha

Common misconception #1: Kama Sutra is a sex manual

‘Whenever the words “kama sutra” are mentioned among people who are not truly knowledgeable of what the book is all about, the usual reactions to be found among them include, but are not limited to, lewd and raucous jokes, hushed and embarrassed whispers, and lots of blushing.’ — THEORIGINOF.COM

The Kama in Sanskrit is a pleasure. Not just sexual pleasure but all pleasures experienced through the senses and the emotions. The perfume of a rose, the taste of a well-cooked dish, the touch of silk on the skin, music, the voice of a great singer, the joy of a spring morning, all these are experiences of kama. Kama Sutra could properly be translated as “Aphorisms on Pleasure”.

Vatsyayana’s purpose was to define the whole relationship between a man and a woman. In doing so he offers us a fascinating glimpse into the everyday life, culture, and manners of the Gupta empire.

Of the Kama Sutra’s seven books, only one deals with physical lovemaking. Of that book’s ten chapters, only one deal with sexual positions. One chapter out of thirty-six.

In the late 1980s, an act of cyberpiracy resulted in that single chapter from my translation being circulated widely around the internet, with the result that nowadays a great many people believe that it is the whole of the Kama Sutra.

The famous pirated chapter on postures.

Common misconception #2: Kama Sutra is an ancient text

By European standards, Kama Sutra is a comparatively modern text. Five or six centuries before Vatsyayana, Philaenis of Samos composed a book on courtship and sex which is said to have covered the techniques of seduction, descriptions of sexual positions, aphrodisiacs, abortifacients, and cosmetics.

This became the pattern for later authors, including Ovid in Rome, writing three centuries before Vatsyayana. In his Ars Amatoria as later in Kama Sutra the majority of the work is devoted to teaching the man about town what sort of bride to take, how to woo her, how to love her, including physical lovemaking, and how to keep love alive.

Let the girl with a pretty face lie supine, let the lady

Who boasts a good back be viewed

From behind. Milanion bore Atalanta’s legs on

His shoulders: nice legs should always be used this way.

The petite should ride horse (Andromache, Hector’s Theban

Bride, was too tall for these games: no jockey she);

If you’re built like a fashion model, with willowy figure,

Then kneel on the bed, your neck

A little arched; the girl who has perfect legs and bosom

Should lie sideways on, and make her lover stand….

If childbirth’s seamed your belly

With wrinkles, then offer a

rear Engagement…” Ovid, Ars Amatoria

Bawdily illustrated manuscripts of the poetess Elephantis traveled with the Roman emperor Tiberius to his retreat on Capri. There is reason to suppose that some of the material in Kama Sutra as in the later Tantra texts, came to India from the West. Probably ideas and traditions criss-crossed in both directions.

[See the book “Tantra: The Cult of Ecstasy”.]

Common misconception #3: Kama Sutra is a sacred text

If the Kama Sutra is neither a sex-manual nor particularly ancient, neither is it, as also commonly believed, a sacred or religious work. Certainly, it is not a tantric text. In opening with a discussion of the three aims of ancient Hindu life – dharma, artha and kama – Vatsyayana’s purpose is to set kama, or enjoyment of the senses, in context. Thus dharma or virtuous living is the highest aim, artha, the amassing of wealth is next, and kama is the least of the three.

Having paid lip service to the higher aims of life, Vatsyayana begins to show us a brilliant and amoral society with pleasures as refined as those of ancient Rome or Athens. Religion is soon forgotten. In the Kama Sutra’s list of desirable accomplishments, chanting from sacred texts comes between composing tongue twisters and quoting from the latest plays.

True, the citizen is urged to take part in drama festivals staged in the temples of Saraswati but he is expected to throw parties for the actors. Other named festivals are those of Shiva, Ganesh, and the Night of the Yaksha (which Burton misread as “aksha” or dice, thus giving rise to the nonsensical instruction to spend nights playing dice).

The reader is specifically told to avoid secret sects which practice degrading rituals and this may be a reference to tantric practices. (For a discussion of the origins of such practices see my book “Tantra: The Cult of Ecstasy”.)

Many wish to believe that Vatsyayana wrote with a high moral purpose, but the evidence of the text is to the contrary. The Kama Sutra is amoral from beginning to end, advocating all sorts of opportunistic, selfish, and unsocial behavior, including seducing the wives of friends and strangers, raping peasant girls and, if one is a king, capturing and enslaving any woman one likes. In its unabashed advocacy of whatever conduces to one’s own advantage, it is like Kautilya’s Arthashastra. The closest thing in western literature is Machiavelli.

Concerning Arthashastra, see this bizarre story.

Life in the Gupta Empire

Gupta cities were as sophisticated and cosmopolitan as anywhere in Greece or the Roman empire. The emperors were enthusiastic patrons of the arts. Under their rule, poetry, drama, dance, and music were well funded. Large cities had libraries and art galleries. Tempera masterpieces on the walls of the Ajanta caves demonstrate that Indian painters of the period were the equals of their Greek and Rome counterparts.

Victorian art critics were astonished by the Ajanta cave paintings, which were discovered by a party of British soldiers. The famous Dr. Fergusson said that in their use of chiaroscuro and perspective, their deep rich colors, and their ability to capture the most delicate expressions, the Ajanta painters were not surpassed until the Italian renaissance, and in particular not until the madonnas of Bellini.

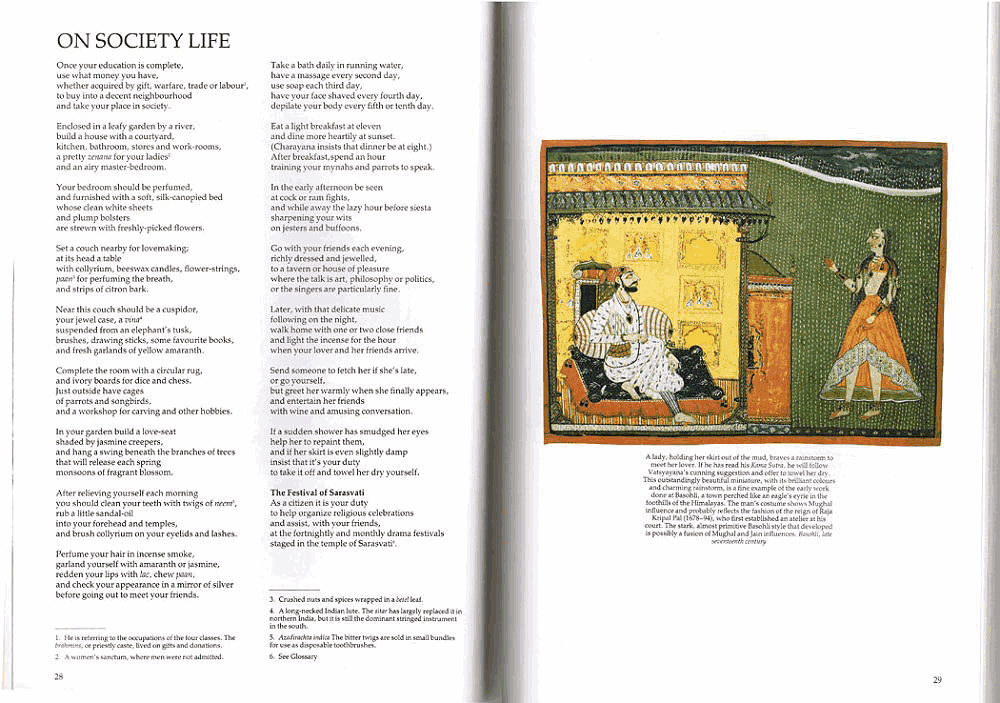

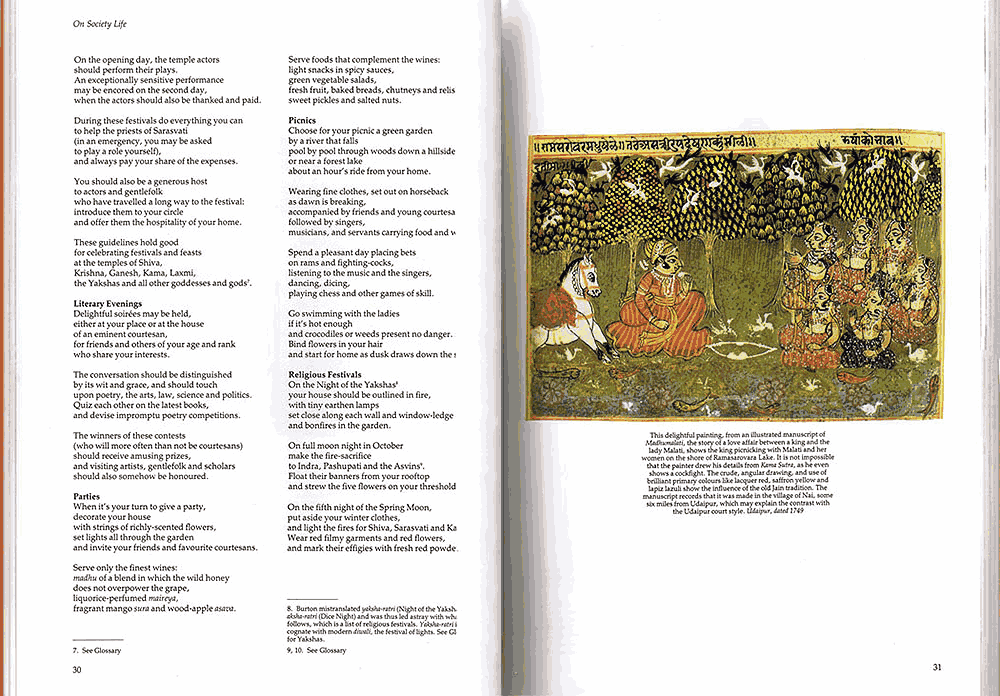

On society life

Vatsyayana gives us a fascinating description of the daily life of a wealthy man, who sleeps in a bed strewn with fresh flowers, perfumes his body with sandalwood, and outlines his eyes with collyrium. He spends his days teaching parrots to talk, attending cockfights, and visiting inns or pleasure houses to talk of art, poetry and listen to singers. Later, he will welcome his lover to his beautifully appointed house, and if she has been caught in a shower of rain, will offer to towel her dry.

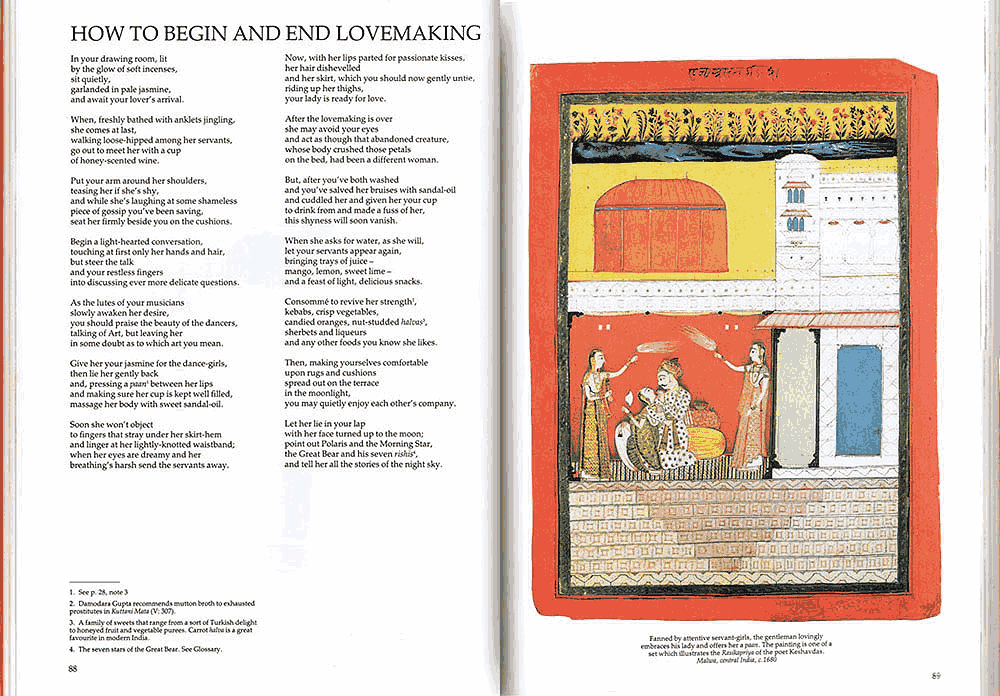

The advice on beginning and ending lovemaking is one of the tenderest passages.

Let her lie in your lap

with her face turned up to the moon

point out Polaris and the Morning Star

the Great Bear and his seven rishis

and tell her all the stories of the night sky

Life in a wealthy Indian household, c350CE

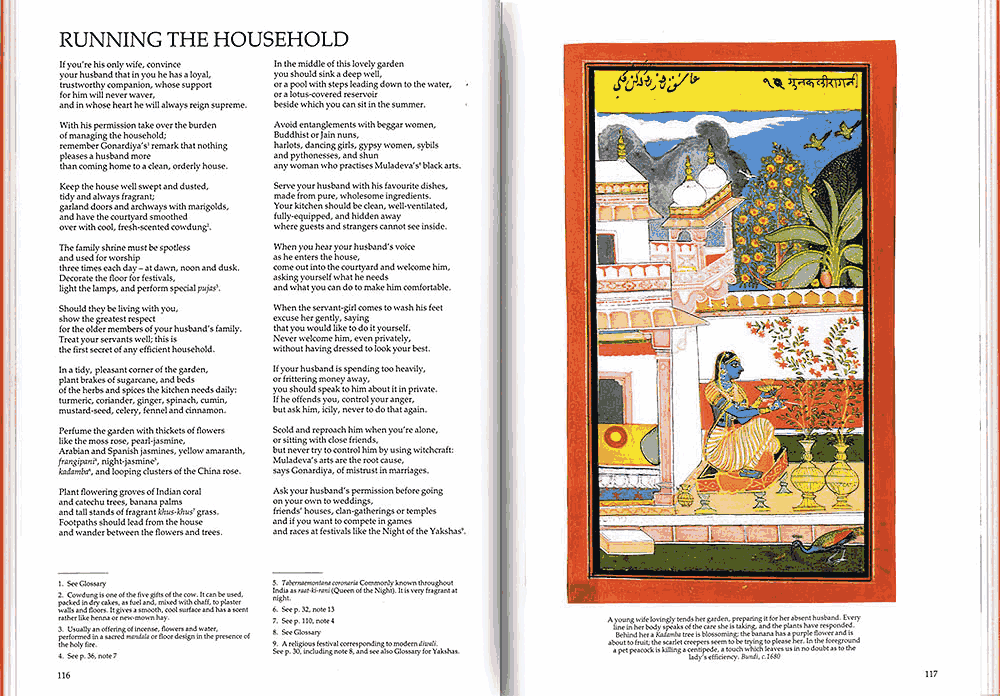

Flowers and herbs for the garden, supervision of kitchen and servants, production of food and drink, and ways to practice small economies – all these are the domain of the woman of the house. Let her fulfill her wifely dharma, says Vatsyayana, and she will be spared the curse of having co-wives.

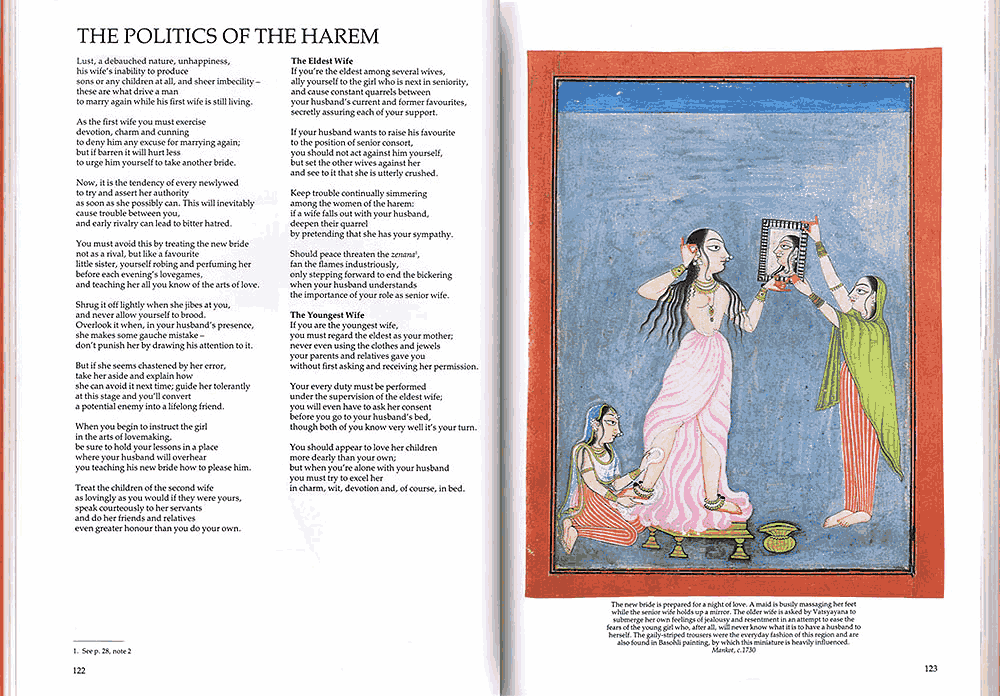

Should a woman be unlucky enough to find herself one of a number of wives, Vatsyayana offers her advice on how to act to her best advantage. Instructions for manipulating other women and their common husbands are given with complete sangfroid. The Kama Sutra is a book for pragmatists

The 64 arts and sciences

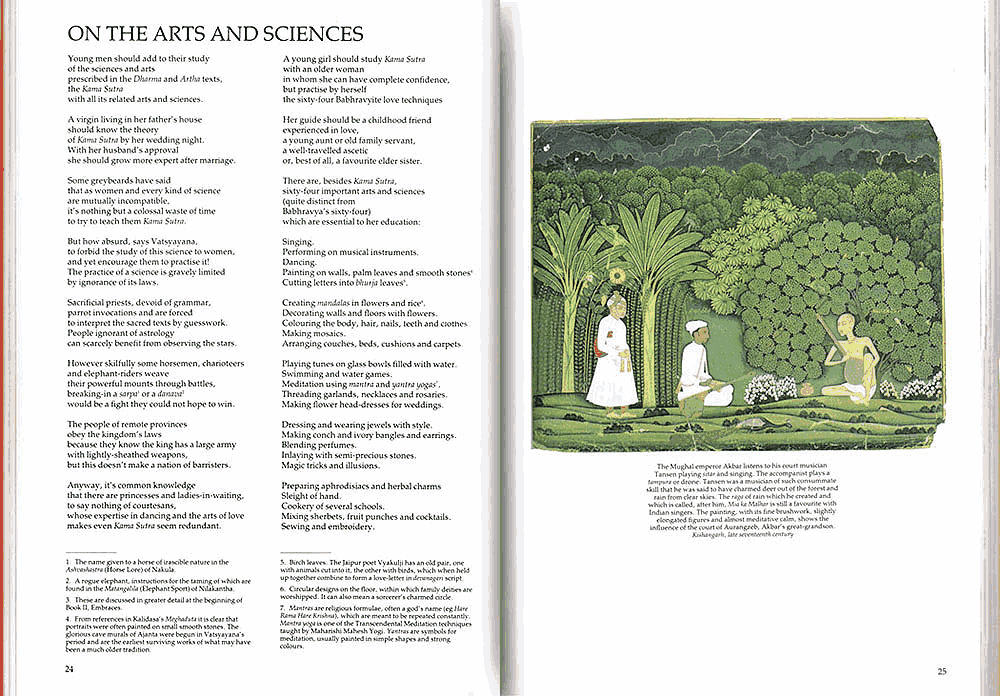

Fashionable men and women were expected to be proficient in sixty-four arts and sciences which included performing on musical instruments, blending perfumes, horticulture and plant medicine, inventing a private language, and wood-carving. Indian courtesans, like their Greek counterparts, were highly cultivated, sophisticated people. Vatsyayana promises, in a remark reminiscent of Ovid, that a woman who knows these arts can always make a good living.

A tradition of erotic art

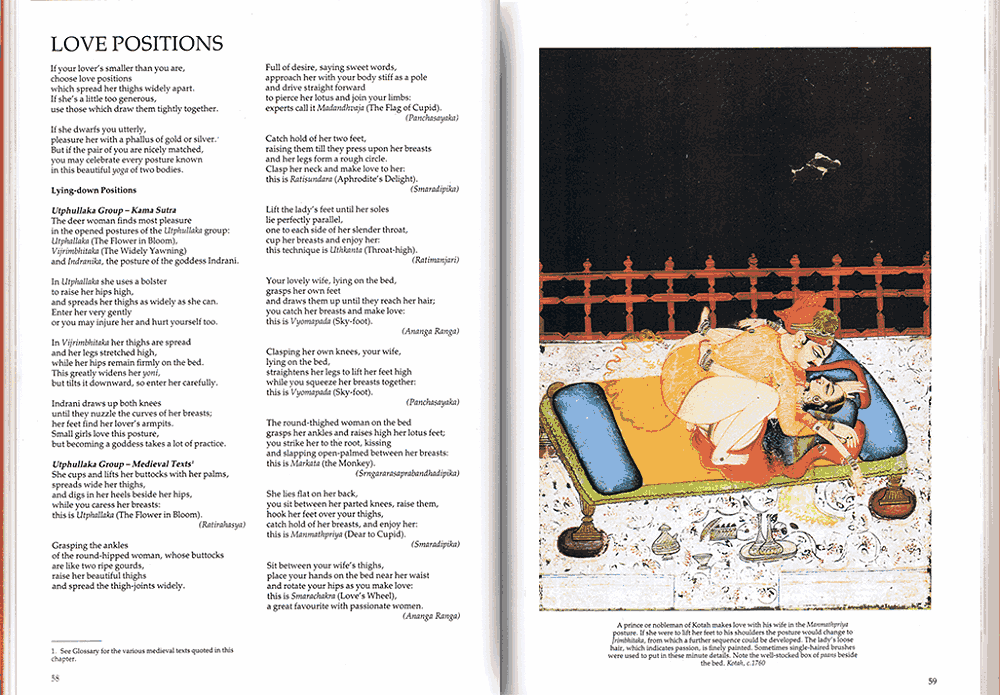

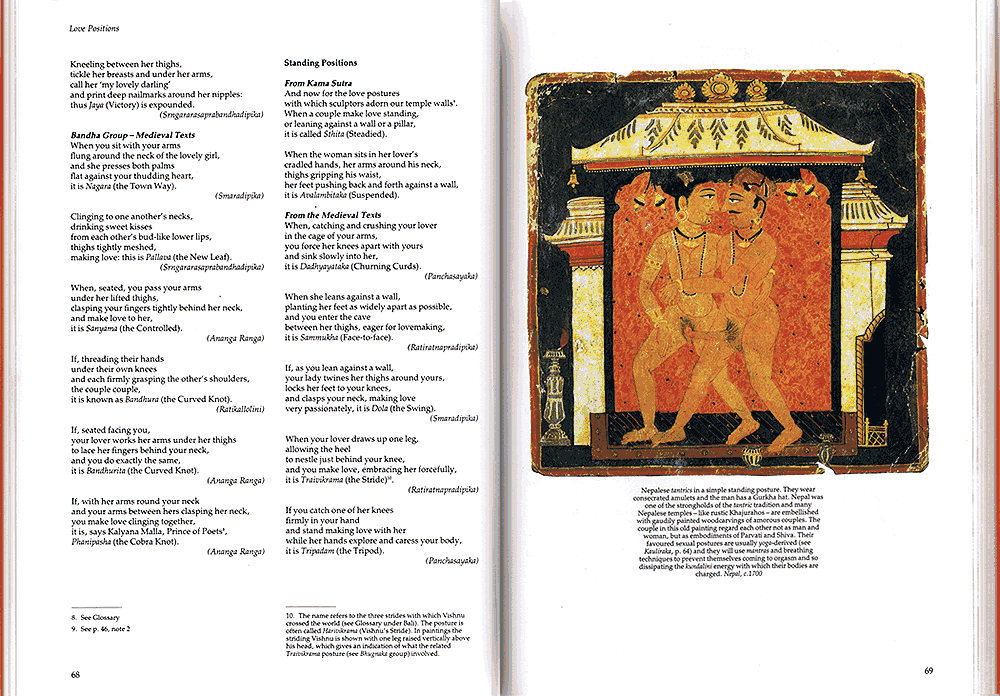

A series of rather extravagant lovemaking postures are described in the Kama Sutra as chitrasanas or “picture-postures”, presumably because they were favourites in the art and sculpture of the Gupta period.

The sculptors of the Khajuraho temple complex built by Chandela kings in the 10th and 11th centuries CE were surely influenced by the Kama Sutra, which had by then been known for several centuries. However, they may have had a hard time deciphering Vatsyayana’s text, which was composed in sutras, or aphorisms, condensed to the point of inscrutability.

Like a mare cruelly gripping is the Mare, it needs practice.

Meanings of sutras like this one had to be explained and expanded by commentators. The Jayamangala commentary which accompanies most Sanskrit editions of the Kama Sutra was written in the 12th century, some eight centuries after the original. For the sutra above the Jayamangala adds that the “Mare’s Trick” was perfected by courtesans and popular among women of the Andhra region of south-central India. When you read the translations of Burton and others you are in fact mostly reading the Jayamangala.

A new approach to translating Vatsyayana

I decided to take a different tack and expand the sutras into stanzas of rhythmic prose, bringing in facts, ideas, and imagery from the commentary and from poets whose work explores the mysteries of kama, above all trying to recreate and vividly bring to life the era and culture in which Vatsyayana lived and wrote. Mine, therefore, is not a literal word-by-word translation but more an idea-by-idea reconstruction. The miniatures were sourced by my wife during a three-month trip we made to India in 1979.

Our translation was published in 1980 and, as mentioned above, is the well-known version whose chapter on lovemaking positions can now be found right across the internet. Since then, there has been a wonderful edition of the Burton text by my old friends Mulk Raj Anand and Lance Dane (1982) drawing on Lance’s huge art collection. I can thoroughly recommend it.

However, the version my wife and I created during our trip to India – which was also the first to use Indian miniatures to illustrate the text – remains unique in its approach. The English edition has now been in print continuously for thirty years and has been re-rendered into languages as obscure as Brazilian Portuguese and Finnish.

Article source: http://www.indrasinha.com/books-2/kama-sutra/ (Unfortunately, this site is no longer available)

Indra Sinha

Indra Sinha is a British writer of Indian and English descent. Sinha has the distinction of having been voted one of the top ten British copywriters of all time. He is the author of The Love Teachings of Kama Sutra, the 2nd, more modern translation of the Kama Sutra into English (the first translation was by Richard Francis Burton in 1883).